Given that it is Friday, and further to my post yesterday, I thought I might offer a few reflections on St Albert's painting of the Ecce Homo.

First of all, no reproduction can capture the beauty or intensity of the original. This is a painting I am familiar with and have loved for a number of years, but finally seeing the original I was overwhelmed. It seemed to me that it was lit with an interior light that drew me in. It is a work that is meant to inspire meditation painted by a Saint over a number of years as he progressed in holiness and was drawn deeper and deeper into the life and Heart of Jesus Christ. This is a work of love, of intimate love, by a poor man seeking refuge, strength, wisdom and peace in his Saviour. It is work by a man who met the crucified Christ every day, first in his prayer, in the Holy Eucharist and then in his work as he served the poor, the abused and the lost.

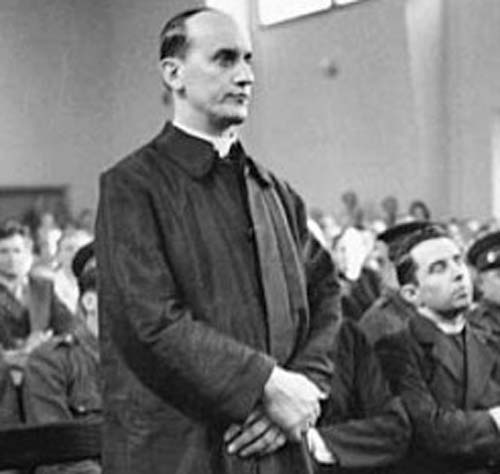

The subject is that moment when Jesus, having been scourged, is brought out by Pilate to face the people who are clamoring for his death. Wrapped in a cloak, a crown of thorns on his head, a reed in his hand, Jesus is a pitiful sight, his back and chest torn open from the scourging, his eyes blinded by the blood flowing from the wounds in his head. Pilate intended to present Jesus to turn the hearts of those who wanted him dead. Fearful of doing the right thing yet also afraid of condemning an innocent man, Pilate wanted a way out, and he thought moving the hearts of the Lord's accusers to pity might provide one. It didn't. Their hearts were closed. And so confronted with the pitiful sight of the once beautiful Jesus, they close their eyes and shout even louder: "Crucify him!"

St Albert intends us to see him, his beauty still intact beneath the agony he bears. We see the marks of the lashes on his chest, the wicked thorns bearing into his head, piercing it. Are our hearts open enough to be moved to pity, even to love? It is love that has the Lord here, suffering his passion: love of the Father who sent him, love of us who need to be redeemed. This is an encounter with suffering, it is meant to make us uncomfortable, make us think. Albert could not escape the sight of suffering - the suffering of the homeless and the poor on the streets of Krakow. It was that suffering which opened his eyes to the sufferings of Christ, and that was the moment of his conversion. This is what Pope Francis is doing when he draws our attention to the poor - we are to see them and see Christ; we are to serve Christ by serving them, and in this service come closer to Christ.

In this painting we see that the Lord is a captive, his hands are tied, there is a rope around his neck, he can go nowhere and he is brought before us. This painting is meant to provide us with a confrontation - we are not meant to escape no more than he can escape. Though we may try, we cannot escape the reality of God, his love and what he has done for us. He has bound himself to us, not merely as our Creator, but as our Redeemer and as our Divine Lover. He is, as Francis Thompson discovered, the "hound of heaven" who lovingly pursues us. Paradoxically, he is the one who allowed himself be caught in order to come to us, so we might see his loving Heart open to receive us.

Reflecting on this painting, I am always drawn to the face of the Lord and what an astonishing vision it offers us. Though he is suffering, his body torn with wounds, bound and being mocked by the crowds, he is serene; his face is the vision of peace. It does not register pain, but rather it is meditative, loving, seemingly content. His eyes are closed, his lips are closed, his brow is not furrowed. This is one at peace with himself and the world. This is one who knows he is doing what is right and good, there is no doubt, no agonizing, just acceptance. This is the Christ of the Father's will. This is the vision of the joyful Christ who understands exactly what is happening and what its fruits will be. This is the suffering Christ who offers hope to all who suffer themselves. Just thinking about St Albert as he painted it, we cannot fail to see that it was painted by a man who was himself at peace with God, a man who himself suffered but understood the significance of suffering, a man who knew the hope that Christ offers through his passion and death. Indeed I often think that in painting the face of Jesus as he did, St Albert had already seen the Face of God and wanted to communicate what he saw so we too will seek that Face and find Christ.

The Ecce Homo is an unfinished work. Yes, it is modern - looking at some of his later paintings I think St Albert was way ahead of his time artistically. As a brother and founder he would come back to the painting every now and again, sometimes urged by his friends, and do what he could to complete it; he never did. It was the only work he kept, and he eventually relinquished it to a friend who asked for it. In a sense it is apt that it should be unfinished- there will never be a last word when it comes to Christ and his passion - these are eternal mysteries. When we look at the suffering Christ we are led to understand the work that has to be completed is that which must be done in us, in our souls. God's artistic work is the creation, redemption and sanctification of men and women, and that is the most important work. Albert's Ecce Homo was completed when he himself, sanctified, entered into the house of the Father where Christ presented him to the Eternal Father: "Here is the man, the brother Albert, in whom I am well pleased". As each one of us reflects on this unfinished painting we are to understand that Jesus wishes to do for us what he did for Albert, we need only surrender to him who surrendered himself to us.

And perhaps another thing we might discern from the painting's unfinished state: we have to encounter Christ for ourselves in the intimacy of our own lives. St Albert leads us to the Lord, but we have make the decision to go to him and until we do we will not have the complete vision or knowledge of him. If we stand back the image of Christ will always be incomplete. We have to enter, we have to say yes, we have to engage with him. This painting, then, may well be a proposal, an invitation, to come closer and seek him who already stands before us.