I recently went to see a dramatic adaption of Wuthering Heights at the Gate Theatre in Dublin with some friends. It wasn't a great performance, surprisingly for the Gate. However it did get us talking about the Brontes and their works. My friends are not fans of the Brontes and the play didn't do much to endear the scribbling ladies to them either. A couple of weeks later I joined these friends for a meal and I brought a movie adaption of Wuthering Heights for us to watch and compare. No joy there either, it wasn't the play that put them off, it was the story. And to be honest, it is a rough story.

I think most of you will probably have read Wuthering Heights, it was all the rage when I was growing up, many teenage girls loved the novel and lamented over the lost love between Heathcliff and Cathy. I didn't really fall under its charm, and when I went to University to study literature our lecturer in Nineteenth Century Fiction was no fan either and directed us away from the Brontes to George Eliot and her masterpiece Middlemarch which is, in my opinion, a far superior literary work, though I do think Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre is also an extraordinary piece of writing. That said I do think Emily Bronte is on to something as she explores the characters of Heathcliff and Cathy and plots their obsessive and destructive love affair. I think Emily's reflection provides us with some useful insights into human obsession, sin and passion.

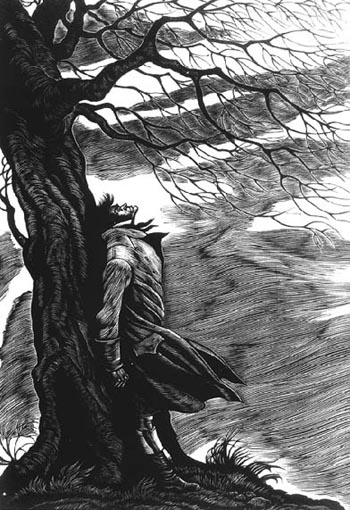

To start with Heathcliff and Cathy are not, in my opinion, heroes in the normal sense of the word, more like anti-heroes, they are not to be regarded for their virtues but rather their moral failures, or more correctly how their moral failures lead not only to their own destruction, but also to the destruction of all those around them. Their unbridled passion, lust, obsession, call it what you will, mingled with hatred, vengeance and jealously, tears their lives apart and the lives of those around them, with the exception of three people: Nellie the maid, who endures; and their children Cathy junior and Hareton who finally escape but do so with deep wounds. Far from swooning at them, I think Heathcliff and Cathy are unlikable figures, repulsive even, not by nature but by the choices they make. So obsessed with themselves and each other, they are distorted, perhaps even grotesque. Given the distorted view many have of love today, I suppose it is no surprise that Heathcliff and Cathy are regarded as romantic figures: there is nothing better, some would say, than the love that is doomed and chosen even though it destroys.

This pair provide us with a warning, a even starker one than that provided by Francesca da Rimini and her lover Paolo; the storm which surrounds Bronte's couple seems even wilder and hellish than that in the second circle of hell. Unbridled passion is dangerous, it can destroy the soul, and not just one, but many. It is like a tornado, it careers through the landscape of humanity wrecking whatever it passes. Passion without reason and virtue is dangerous.

There can be a virtuous passion, a passion that leads not to destruction but to creativity, beauty, holiness. We see this in the Saints we have just celebrated, notable among them St John the Apostle. Indeed we find passion enshrined in the Scriptures in the Song of Songs and in the writings of the Saints, chief among them for me, St Teresa of Avila, St Therese of the Child Jesus, St John of the Cross and St Catherine of Siena. There can be no denial that passion is a human experience, an extraordinary emotion, but it must be graced, redeemed, oriented in the right direction so as to be fruitful.

The passion of Heathcliff and Cathy was not fruitful, like the physical landscape that surrounds them, it is barren, it produces ghosts and unrest. Cathy's ghost at the window and Bronte's noting at the end of the book, that Heathcliff's ghost also walks is no suggestion, in my view, that love lives forever, rather that their souls may well be cursed to wander aimlessly, restless, eternally unsatisfied, lost. I sometimes wonder if Emily Bronte has, in the end, put her untamed couple in hell?

Is Emily telling us to be careful, or is she only lamenting the lost love of Heathcliff and Cathy unaware of a deeper movement underneath it all? Perhaps. But that warning is one of the things I take from this novel. My friends are unconvinced, one remarked that if this was Bronte's intention she did not have to do so in such a negative and destructive way, in a way that might inspire unwitting fans to take the same road. Well, that means has been employed in art for some time. Milton in Paradise Lost did the same with his character of Satan, as did Burgess in A Clockwork Orange with his bunch of miscreants. Shakespeare does the same in his tragedies, notably Macbeth, though in that case it was an exploration of how a noble figure is destroyed by his failings and the corruption is all too clear so to provide a warning rather an example to be imitated. Modern literature loves the anti-hero, Emily Bronte is just an early exponent of that trend.

Anyway, these are just a few thoughts. If you have any ideas yourself you can share them in the comments box. No fighting now!

_001.jpg)

![[6a00d8341c571453ef010536590704970c-320wi.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgzy1Jx-xgOefOdHbvIB8-269pVSgJU4msQ89U7SL_0TmhaQd-etCwVaX_LNdIEX1kIBOyMQGbEos3w4RplyetbPBNORaFe76tH8Qw_MKyJiDVZQNbXShqDX9SqK38Ui242ui3ka_pEYYQ/s1600/6a00d8341c571453ef010536590704970c-320wi.jpg)